Spotify Examined: What their report really says December 19th, 2013.

As 2013 comes to a close, Spotify has published an in-depth article about their business. The report, Spotify Explained, lays out the economics of their business in great detail. It even debunks some long-held beliefs about how Spotify works (e.g. they don't pay per play, so most of your money goes to popular artists no matter how indie your listening habits are).

However, as an incurable geek, I had to take a closer look at the data, and I found a number of omissions and misleading claims throughout the report. A casual reader might come away believing that without Spotify, the music industry is doomed. In fact, even Spotify's data suggests that isn't true. The scoop is below, along with background if you haven't read the report already.

Better than it's been

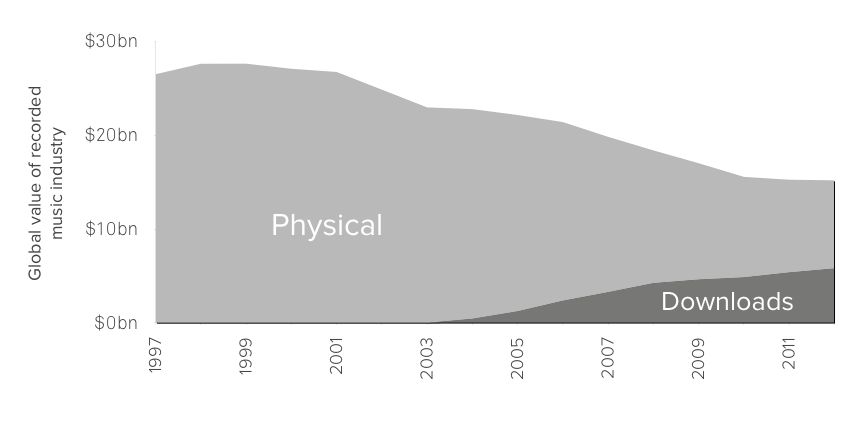

Spotify starts off their report with a depressing looking graph:

Along with that image, they include the following caption:

The decline in the recorded music industry over the last 15 years. Digital downloads have not been able to make up for the decrease in physical sales. Spotify is attempting to restore much of the lost value by convincing music fans to pay for music once again.

Clearly the recorded music industry is no longer at its peak. But Spotify's claim here that falling physical sales dominate the rising digital sales isn't supported by their graph. At a glance, it appears the downloads are instead growing just fast enough that the industry is break even now and could be growing soon.

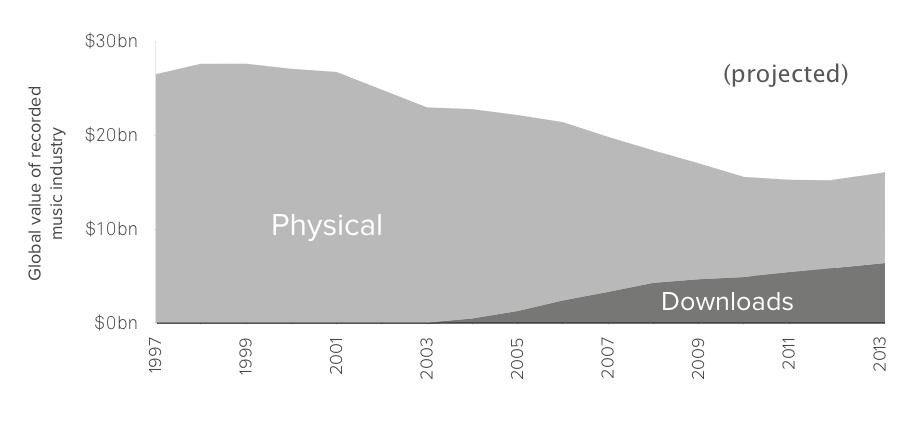

Not willing to trust my eyes, but also not privy to Spotify's data, I went ahead and got the equivalent by simply counting the pixels [1]. Assuming their graph is accurate to scale, the trends over the last few years look like this:

| last 5 years | last 3 years | last 1 year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | -$1.4B/yr | -$1.0B/yr | -$0.5B/yr |

| Downloads | +$0.5B/yr | +$0.4B/yr | +$0.4B/yr |

What's interesting is that downloads have grown pretty steadily year-to-year. And while physical sales per year have fallen, they're falling less and less each year. We're set to soon see growth of digital sales eclipse the contraction of physical sales completely. Which means the graph, if expanded a bit, might look like this:

It goes up a little bit! I'm willing to believe Spotify didn't expand the graph to 2013 because they didn't have the data. But their narrative is a lot stronger if they don't mention this trend. Even without revenue from streaming services, the record industry's future is looking more positive than it has since the turn of the century.

Apples and oranges

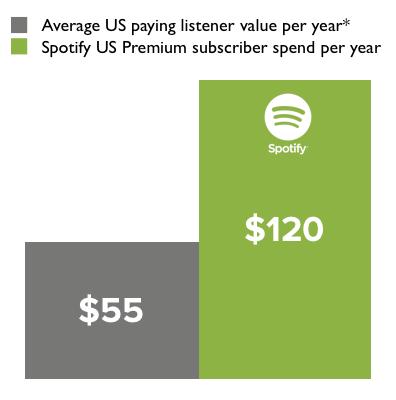

One of the charts in the report compares the revenue per person among Spotify's paying U.S. customers to that of the average U.S. music buyer. The Spotify side is more than twice as tall. Impressive.

Spotify is playing a little fast and loose here, though. A Spotify Premium user isn't the average music fan. Only 25% of Spotify's active user base pays for the Premium service. (Here I'm assuming the global rate applies to the U.S.—my guess is the percentage is actually smaller, but Spotify doesn't say.) This comparison doesn't make much sense.

A fairer comparison might have been the average U.S. citizen against the average Spotify user, since both include people not really paying for music. Spotify does make that comparison later in a similar chart, but it's buried three more pages deep. I presume it's buried because the ratio is the merely good looking 1.6x instead of the incredible looking 2.3x.

An even more fair comparison might account for the many people using Spotify (paid and free) who are spending less on music than they would without such streaming options. Trying to estimate this cannibalization effect is pretty tricky, but it's certainly not zero.

Conservatively, let's just take the non-Premium users. In a year, Spotify makes about $14.67 per advertising-supported user [2], but those folks if considered just typical Americans would spend $25 on average [3]. That's just over $10 per year lost for each cannibalized person. Given that sort of loss per user, it's hard to be sure that if Spotify takes over all digital music it will be a win for the industry.

Revenue matters

Spotify doesn't talk much about the most important number of all: total revenue sent to rightsholders. I suspect they omitted this information because, as it turns out, Spotify's payouts don't really compare to those of services they categorize as "poorly monetized formats."

First, as the initial graph above indicates, sales of physical media like CDs and vinyl are still absolutely gigantic in terms of revenue. Those sales aren't due to Spotify—why buy when you can listen to anything anytime? Services like Pandora and terrestrial radio don't cannibalize physical sales that way, and instead are promotional channels that create purchasing intent.

Second, even sales of music downloads are more impactful than Spotify. In their report, Spotify announced that they've paid out a billion dollars over the last seven years. Meanwhile, downloads paid out something like $5.7 billion just last year (again, according to the pixels). The report belittles the ~$5 per month the average American spends on downloads without acknowledging that they're talking about 90+ million people. That's about twice the number of subscribers to cable nationwide, for scale.

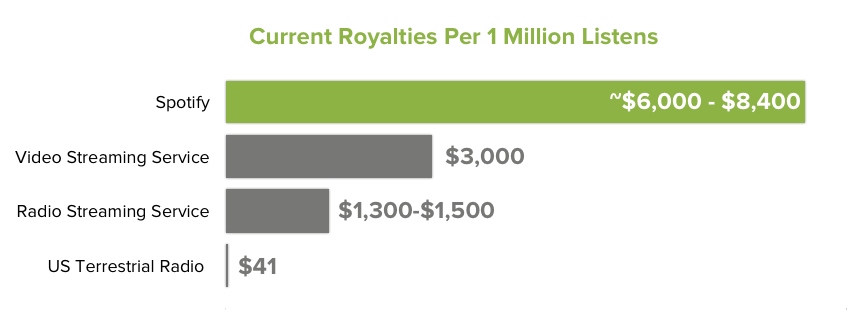

Third, they have this fun chart, where they list "Video Streaming Service" as a competitor. (That's YouTube, if you weren't sure).

The graph estimates the earnings for YouTube video views at $3 CPM, which agrees with claims from independent sources about typical partner videos. But the record labels are no typical partners.

In fact, YouTube has done some heavyweight distribution deals with the major labels (e.g. the omnipresent VEVO brand). The labels have a tremendous amount of negotiating leverage against YouTube (if only due to the threat of lawsuits). It's hard to believe that top artists are getting the same deal as the average YouTuber.

Assuming the CPM is indeed lower on YouTube, that deficit seems more than made up by the fact that YouTube has over a billion users worldwide. No wonder there are reports that artists make more from YouTube than from streaming services [4] [5]. And the visual nature of YouTube adds an opportunity for artists to collect endorsement revenue either through sponsor-paid ad deals or with product placement in music videos. That's yet more money Spotify isn't sending anyone's way.

Wrapping up...

All of the above criticism aside, I'm still optimistic about the future of recorded music. Streaming services like Spotify are, of course, a big part of that optimism. And if Spotify even reaches half the goals they're shooting for, they'll be a substantial driver of revenue for the industry. But now that we have the numbers, we know they aren't there quite yet. Meanwhile, digital downloads combined with physical sales are making $15B per year and are poised to be growing by a half billion per year. Along with the substantial and growing revenue from concerts and merch, the industry seems to still be pretty healthy.

So, maybe Spotify-style streaming isn't the savior of music, but merely one of many revenue channels in an overall growing industry.

I'm @__aston__ on Twitter. Send me comments there or leave your thoughts on Hacker News.

- No, not by hand... I wrote a Python program to do it for me. ↩

- Spotify claims their customers (free and paid) are worth $41/year (see graph in [3]), and we know Premium users are ~25% at $120, giving us $14.67 per free user. ↩

- The Spotify-provided graph with these numbers is here. ↩

- Justin Bieber, Lady Gaga, Rihanna Music Videos Most Viewed On YouTube ↩

- Report: Spotify Paid Lady Gaga $167 For 1M Plays ↩